*UPDATE: One day after this story aired on CBS19, a group of donors gave $500 to the Dickson Colored Cemetery fund.

On a hill in a quiet and rural East Texas city, a spirited and historical story is waiting to be told.

"I think it's a thing where too many times, history is not written correctly," said Gene Turner, a man who has dedicated the last several years to preserving a historic piece of land near Gilmer.

This piece of history begins with a story that began more than a century ago between the green shrubs and dated trees.

"Something like this that needs to be done, and nobody never says anything," Gene's brother Eddie Turner said. "Well, what happened? Nothing, since we knew about it, let's get out here and get it done."

In its early years, Gilmer was a suitable engine for some of East Texas' economy, serving as a cotton-ginning center and several sweet-potato farms.

While one Texas town was booming, another lone star city was trembling in devastation.

On September 8, 1900, the "deadliest natural disaster" in American history struck Galveston. Historians call it the "deadliest" because a category four hurricane destroyed 3,600 buildings and killed 6,000 to 12,000 people.

Without family members to turn to, a home to find solace or food to eat, orphan children began their journey out of Galveston and into East Texas.

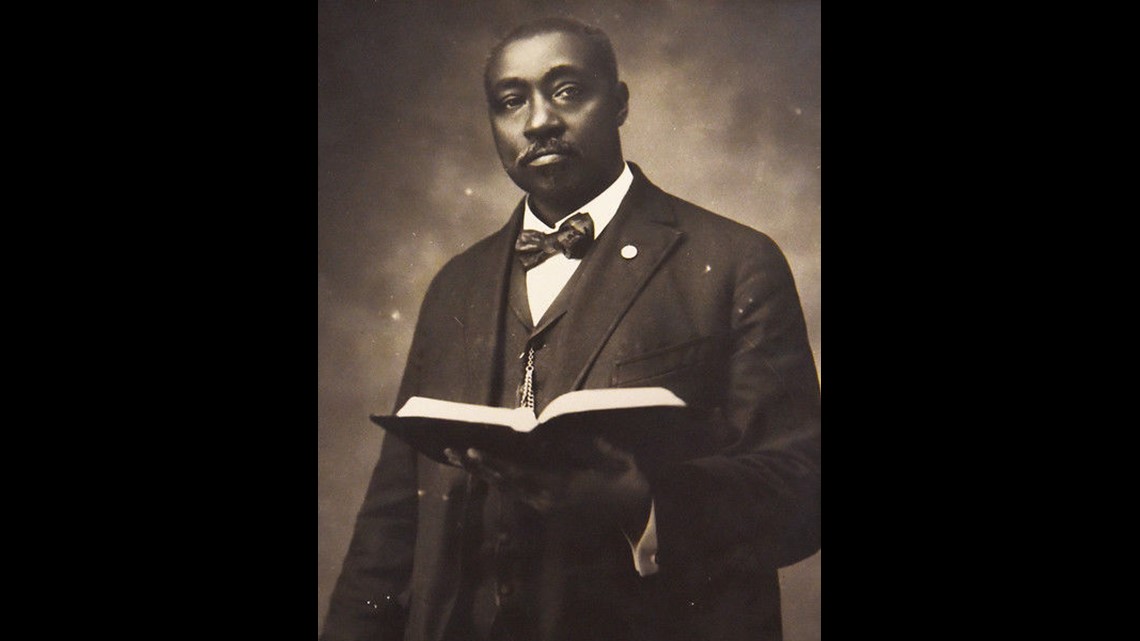

That same year, as many wandered to find hope, a Dallas based minister, inspired by Booker T. Washington, wanted to help.

By the spring of 1900, another suitable engine began.

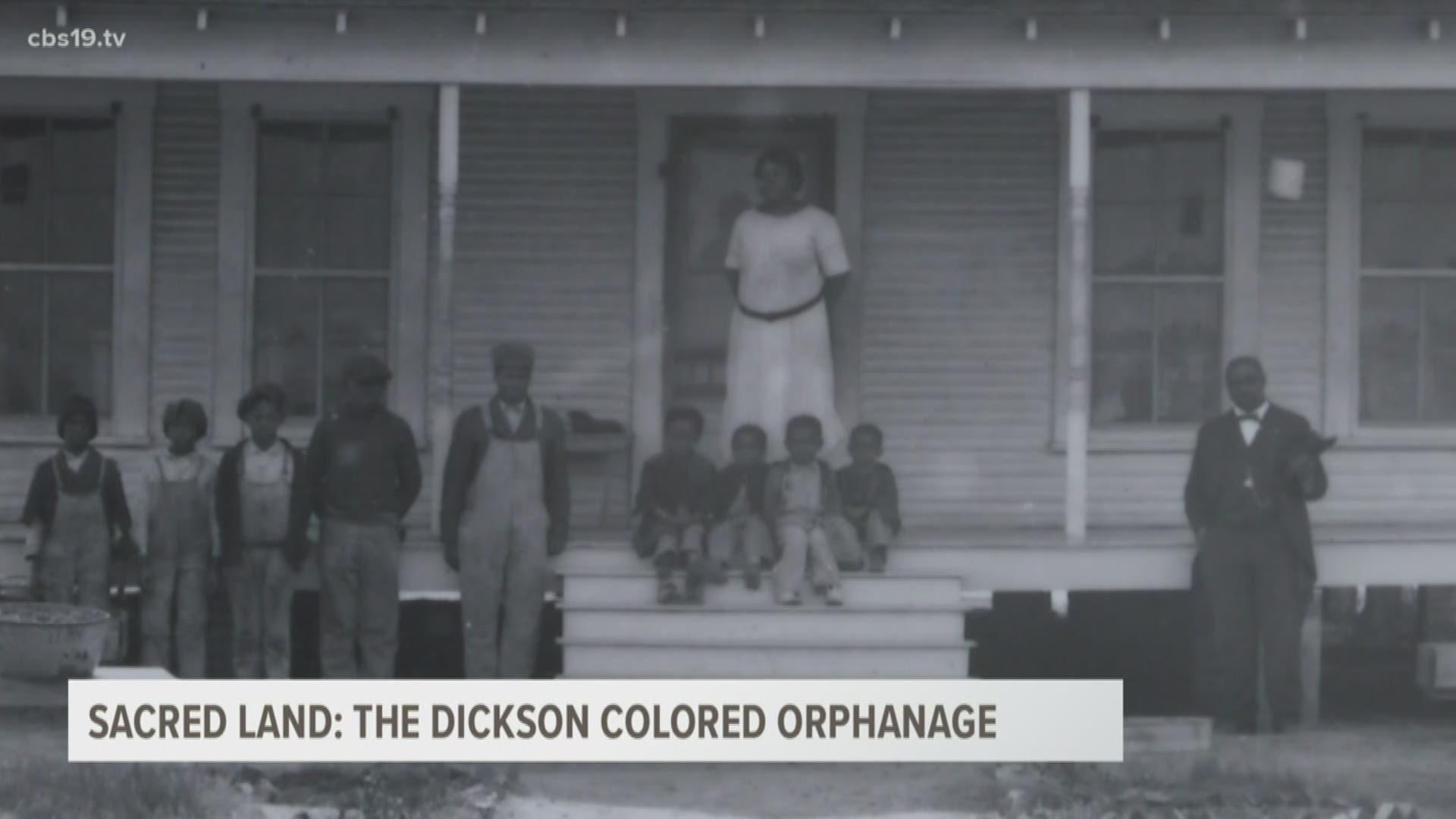

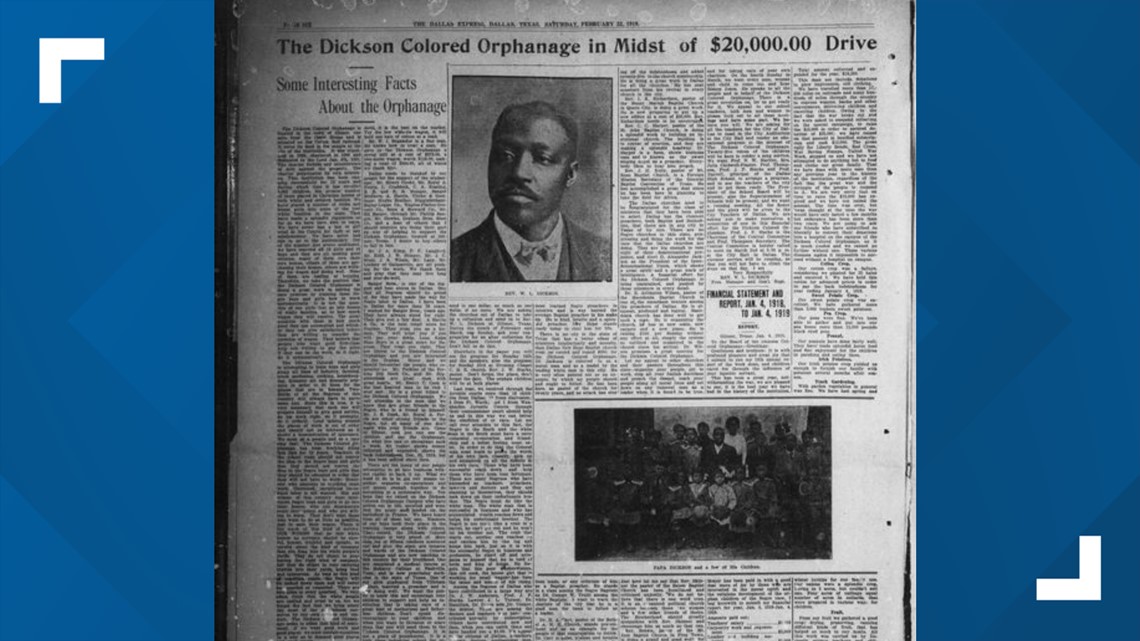

Reverend William Lee Dickson spotted young, mother and fatherless children, wandering Texas roads. He extended his hands to those in need and provided food, shelter, clothing and job training. Children slept in shacks and learned about farming and hard-labor.

During a meeting with African-American Baptist Ministers, Reverand R.C. Bucker, R.C. Buckner, J.M Dorrah, O.L Halbert, G.W. Hood, H. Hudson, A.R. Griggs, Henry Greenwell, D. H. Scott, John Marshall, and N.A. Seales and other religious organizations decided to establish an orphanage.

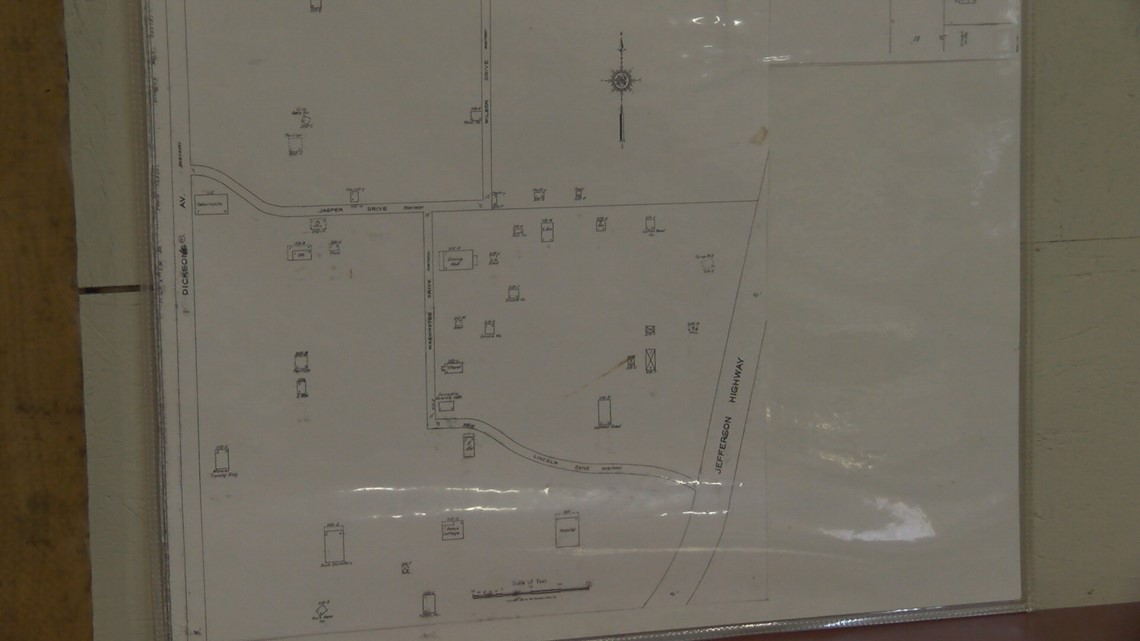

Upshur County residents, including former Confederate Officers, donated 70 acres of land; Gilmer was the chosen soil.

According to the Texas State Historical Association, on the Jan. 4, 1901, Dickson's Colored Orphanage opened its doors. The first and only colored orphanage in East Texas.

"I feel and imagine what they have what they went through by having no mother, no father, that is very touching to me," Eddie added. "And that's what I think when I walk across the cemetery, I think of it."

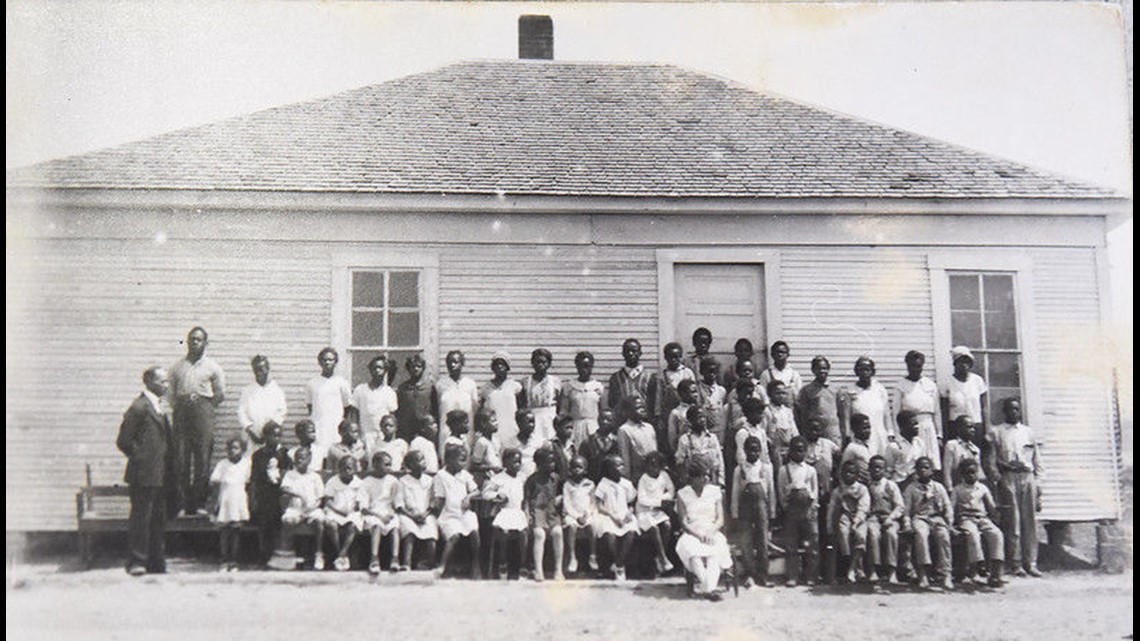

The site went from 70 acres to 800 acres in its final days. Starting with six children, the orphanage eventually housed 200 children on record.

Starting with a shack or two, the institution grew to have at least 40 buildings, including a blacksmith, mechanical, engineering shop, laundry room, cotton shed, potato curing plant, bakery and dining hall.

Eventually, the orphanage become a privately owned housing facility, farm site and educational institution.

Many of the students and residents would learn domestic work, industrial labor, and farming. Some girls were eventually placed with families as cooks. Dickson once stated his goal of raising up students was not to make them preachers or teachers but some of the best servants to maintain the traditions of the "Old South."

Some were members of a co-ed choir. They would sing hymns and songs at churches around East Texas and collect monetary donations to help pay for the upkeep of the orphanage.

Boys were sent into the community to pick cotton for white farmers in preparation for their adult lives. Other residents married and found their place in the world as regular citizens.

So how did a reverend's vision to extend a hand for a generation in need, hope, and education turn into a once forgotten story in Gilmer?

"You see where people [come] from different countries, did different things. [But] we don't know what they did. But somebody here did something great," Gene said.

As the founder's health started to deteriorate, so did the orphanage.

On December 15, 1922, a mysterious fire demolished the boys' dormitory. The organization needed $107,000 for renovations.

About two months after the fire, in a plea for help, Dickson wrote a letter or advertisement that read:

"Persons from every walk of life is being asked to assist in this effort. We must have fire protection. We must have a steam heating plant. We must have electrical lights."

Fighting through turmoil, the orphanage survived on charitable donations. Sadly, a few years later, devastation struck again.

In October 1929, the girls' dormitory burned down. With nowhere for the boys and girls to lay their heads and donations running thin, Dickson had to make a decision. He decided to turn the facility over to the state.

Texas representatives visited the site to survey the area.

According to reports from the Senate's 41st regular session on January 8, 1929, Senator Polland sent the following resolution:

"The property is suitable for a state orphanage for colored children. The State of Texas desires to show its appreciation of its colored citizenship by making ample provision for the maintenance, education, and training of its indigent colored children."

In exchange for debt, the deed of the orphanage would be handed over.

Three months later, the state made another trip to the Dickson Orphanage before agreeing to take over the building, this time with a different outcome. According to the House of Representatives:

"The campus was poorly cared for. Four buildings for the boys and girls were very scarce of bedding and very crowded. In one instance, eleven beds were in one room but three to four boys shared one each. Children did not eat for days, babies were under-nourished. Students worked on the farm some days and went to school other days."

A request for $250,000 was recommended for proper equipment and maintenance in order for the State of Texas to take over the site.

A report from the House of Representatives went on to say:

"It would be very unwise to establish a State Institution. We, therefore, recommend that the legislature do not accept the offer."

Eventually, in 1930, The Texas Legislature voted to take over the orphanage, changing its name to the Gilmer State Orphanage for Negros, in hopes it would eventually be moved to Austin. As his health worsened, Reverend Dickson decided to live with family in Hearne, where he died in 1933.

By 1944, the State's Board of Control took over with an average enrollment of 100 children per year. Still, under the State's supervision, legislatures failed to fund the organizations for fireproofing and reparations. Ultimately, the state decided to transfer students to Austin's Texas Blind, Deaf and Orphan School.

Seventy-two acres of the lost home of hope was given to Texas A&M University for a sweet potato farm. Today, a portion of that farm is still visible, but most has faded into history.

All that is left of the Dickson's Orphanage is weathered headstones for Sallie Dixon and J. W. Washington with dozens of other nameless individuals.

"This is a historic site. Hey, look, this is Gilmer. That's what we've been looking at. This is Gilmer, let's make Gilmer shine. That was the bottom line," Eddie Turner said.

Gene Turner is used to visiting various cemeteries to spruce them up. Gene and his brothers, Eddie and Wilson Turner and friend Huey Mitchell, stumbled on the once-forgotten history in 2014.

"We start asking the questions about this cemetery," Gene Turner said. "Well, nobody knew nobody want to get up and do anything. So then my brothers and I, the committee, said, we'll find it."

"Finally, I come up to a gentleman," Wilson Turner remembered. "He said 'I know where it's located. I'll take you.' We came over here and we drove through the cemetery, not realizing it because it [had grown] up so bad," Wilson Turner said.

"It was a dump ground," Eddie Turner remembered. "There were automotive parts here and I've just overgrown brushes and drama just if you can tell it was here."

With the help of local churches, and other family members and friends, the site was cleared away and established as a historical site by the Texas State Historical Association.

"So from this part on, this will always be a cemetery," Eddie Turner said.

"Above all, we see that these people that was buried here, have a found resting place that are being cared for and that means the world and all to me," Wilson said.